A sermon given during Choral Evensong at St Paul’s Cathedral on Sunday 17th March 2024, ‘Passion Sunday’ - Lent 5 (Year B) based on the text of Romans 5.12-end

Thank you to the Dean and Chapter and the Bishop of London for inviting me to speak here in this beautiful cathedral church. I hope they won’t mind too much if I spend the next few minutes talking about another one I’ve visited!

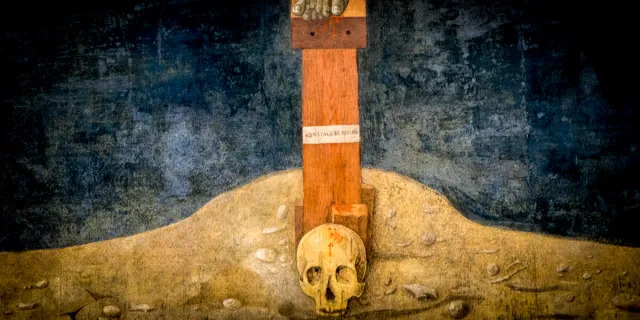

The church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem is built around the sites of Jesus’ crucifixion and resurrection.

The hill on which the cross of Jesus is said to have stood is now contained within the walls of the church. Imagine a hill right there under the dome!

Today, just part of the ragged rock is visible through a glass case. Most of it has been levelled off, adorned with sumptuous marble floors. The walls and ceiling of the chapel that now surrounds the hill are covered with gold mosaics, which glimmer in candlelight.

At the top is a small altar, which covers a hole in the rock in which the cross of Jesus is said to have stood.

A

priest with a very long beard stands nearby - like a sort of holy bouncer. His

job is to make sure that the thousands of pilgrims who make their way up to the

chapel, each get the chance to crawl under the altar and touch this most holy

ground. Calvary. The place where Christ was crucified.

Once

you have reversed out from beneath the altar (pilgrimage can be a very physical activity!) you are ushered down some narrow steps on the other

side of the hill.

Nearby

is a doorway that leads to a space carved under the hill. The Cave of Adam. It

couldn’t be more different than the chapel upstairs. Primitive. Bare stone

walls. Dark. Deserted. Nobody wants to be here - no need for a security priest.

This is the site where, according to early Christian tradition, the remains of

Adam - the first human - lie.

Here,

architecture is used to explore scripture and tradition. The arrangement of the

Chapel of the Crucifixion and the Cave of Adam below it, give physical form to

the passage we heard just now from St Paul’s letter to the Romans - in which we

are presented with an overview of human history described in two ages or epochs

defined by these two men - Adam and Christ.

The

age of Adam. Named after the one who disobeyed God by eating the forbidden

fruit in the Garden of Eden. This era of human history, St Paul says, is

defined by trespass, condemnation, judgement, sin and death.

And

the age of Christ. The Son of God whose resurrection heralded the start of a

new era, defined by grace, righteousness, salvation and the promise of eternal

life.

These

two chapels in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem are arranged like

geological strata. The layers mapping out each age of human history that St

Paul describes. The primitive, dark age of Adam beneath the glorious age of

Christ above.

This

ordering of human existence didn’t just affect the buildings of the church - it

pervaded deep into the life of it’s gathered people - affecting how they

thought - and how they related to each other and to God.

Documents

from the medieval era of European colonisation reveal how the men who

travelled to new lands saw themselves - and people with white or lighter skin

like theirs - at the top of this hierarchy of salvation.

What

they described as the alien, primitive people they encountered had little or no

hope of ascending to the same level.

A

perspective of privilege that today

is perhaps more deeply rooted than many

of us care to admit. There are those who - perhaps unconsciously - still seek

to determine the salvific potential of different groups of people. To attempt to

control, to limit God’s grace.

This

perspective is, in fact, one of the issues that Paul was seeking to address in

his letter.

The

small house-churches of the early Christian community in Rome, to whom Paul

wrote, probably numbered in total no more than those gathered here today.

Phoebe

- a deacon in the church - was sent by Paul to read out his letter. In each

house she would have stood facing even

more of a motley crew than I am looking at now! A far more diverse crowd!

Many

of them had grown up obeying Jewish laws and customs - and

still held these dear. Perhaps they felt that as Jesus was Jewish, their

experience, their knowledge of this ancient faith, gave them a privileged

position in the new Christian community. Placing them above the rest.

Others

had come to the church as pagans - having previously worshipped a variety of

different Gods, including the Emperor. Perhaps they felt that their experience

as subjects of Rome, their understanding of its systems and structures, gave

them a position of power and privilege, so they looked down on the others.

Paul

says that the tension between these two groups - this judgmental way of

thinking - belongs to the age of Adam - and so it can only lead to death. The

death of the fledgling community. The death of the life God intended his people

to lead.

The

new era - the age of Christ - has begun, he explains.

But the boundary between the age of Adam and the age of Christ is more fluid

than we like to think.

Paul

knew how easy it is for people to fall back - to trespass - into the ways of

old. He urged the church to embrace the reality of the new age - choosing to

accept the free gift of God’s grace. Placing faith in his will for our future.

Learning to become more Christ like. Seeing the world and each other through

his eyes - setting aside our privilege and prejudice. Becoming more gracious -

loving our neighbours as ourselves. Recognising our shared humanity as brothers

and sisters in Christ.

One of the few features in the Cave of

Adam, in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem, is a window which looks

out onto a crack in the wall. It is said that this fissure in the bedrock was

formed by the earthquake at the moment of Christ’s death - along which the

blood and water from his body trickled down to wash Adam’s bones.

It’s

an architectural representation of the power of Christ’s salvation – cleansing the world of sin, right back to the first one. But it’s also a reminder of the fluid boundary

between the ages of Adam and Christ.

A reminder that we are blood relations to

both.

An

uncomfortable truth.

Perhaps

one reason why the Cave is less visited than Calvary above?

An inescapable truth.

One

which confronts us each time we

look around at the world today and realise how often we fail to

recognise our shared humanity. How often we trespass into the ways of judgement

and condemnation,

looking down on others from our positions of power and privilege.

A life-changing truth.

A source of hope for a better age to come

- through faith in our salvation by the blood of Christ. The only means by which we can endure a lifetime of slipping and

sliding between these two ages as we strive to follow our Saviour.

On this Passion Sunday, I am reminded that this truth is the cross Christ has

called me to bear. Perhaps it is yours too?

No comments:

Post a Comment