|

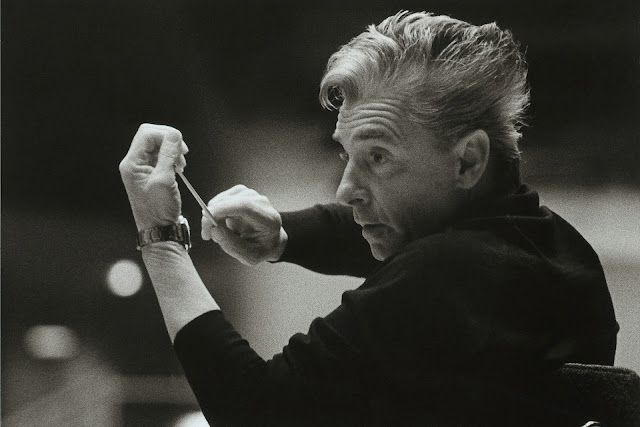

| Herbert von Karajan |

My reflection is on the topic of Leadership and Collaboration - specifically leadership seen through the lens of selection processes. The setting for this story is not the world of politics and the general election - or the Church of England and its selection processes for ordained ministry - but the world of classical music.

Despite his diminutive stature, Herbert von Karajan was a towering figure as a conductor. Perhaps his greatest legacy was as an evangelist for classical music. The most prolific classical recording artist of all time, he sold over 200 million records - at one point his royalties rivalled those of The Beatles. People who lived in areas where they could never dream of hearing an orchestra perform live would have a Karajan record in their home. He embraced new ways of bringing music to people; the first test pressing of a compact disc was his recording of the Alpine Symphony in 1979, with the Berlin Philharmonic.

Born in Austria in 1908, Karajan's formation as a musician fell during the period of Nazi rule. He was a member of the Nazi party and was promoted to a number of prestigious appointments during this time, although his denazification tribunal in 1946 cleared him of any illegal activity. He was appointed “conductor for life” of the Berlin Philharmonic in 1955 and under his baton the orchestra was blessed with success - through critical acclaim and lucrative recording contracts.

The music producer Michel Glotz has remarked "there was a father-son, love-hate relationship between Karajan and the orchestra...there were always those who believed that the glory he was basking in was really their own."

Karajan conducted everything from memory and with his eyes closed; almost as if he was leading the orchestra in prayer; he often spoke of being the conduit of the will or the creative spirit of the composer. Had he opened his eyes he would have seen over one hundred men looking back at him - a situation with which he seems to have been satisfied until 1982, when divisions began to emerge over the composition of the orchestra.

Shortly before a tour to New York, a vacancy appeared in the clarinet section. Karajan promoted Sabine Meyer for the position, a 23 year old Swiss musician he had heard while conducting the Bavarian Radio Orchestra. But while he was "conductor for life" constitutionally he had no authority over appointments, which were governed by a vote of the orchestra members themselves; over half of whom had to support the selection of a candidate beyond their probationary period.

Although the public perception of Karajan was of a leader and personality in control - someone at the top of the hierarchy, in an interview with The New York Times, he explained that he had no control over the orchestra, only influence. While they accepted Sabine Meyer as a temporary deputy, the orchestra rejected her permanent membership, claiming her tone as an instrumentalist did not blend with the other members. Karajan responded by cancelling every appearance and recording with the orchestra, except six concerts that he was contractually obliged to conduct. This had a considerable impact on the finances of the orchestra and its members.

While his candidate for the clarinet position was rejected, during the process of their deliberations, which took over a year, the orchestra agreed to the appointment of their first permanent female member - the violinist Madeline Karusso. But by then Karajan had distanced himself from the orchestra. The time of blessings and bounty was over. After several wilderness years, Karajan eventually returned to the orchestra, resigning just a few months before his death in July 1989.

Today, many orchestras employ blind audition processes - similar to Karajan's conducting style through which he discovered Sabine Meyer. A black curtain is used at some or occasionally all stages of the selection process so that just a candidate’s gifts as a musician can be judged. Critics claim that the sound made as a performer walks to their chair or the way performers of wind instruments breathe means gender can often be discerned by those on the other side of the curtain. Research published in 2018 argues that while gender balance in orchestras has improved as a result of blind auditions, the situation varies considerably from orchestra to orchestra (just 14% of the members of the Berlin Philharmonic are now female) and there is even more variation between different instrumental sections; there are no female trombone or tuba players in the world's top orchestras, and only one female trumpeter.

Karajan was clearly a great evangelist for classical music. But if leadership is about influence and change - was Karajan a successful leader of the orchestra?

Did Karajan have influence and not control as he claimed? Was his punishment of the orchestra an act of protest - or an act of protecting his public image as a leader?

If we see Karajan as a priest and the orchestra as his people what can we discern from their relationship in the years of bounty and the years of famine? What can we learn from the way Karajan recognised the gifts and talents of others?

No comments:

Post a Comment