|

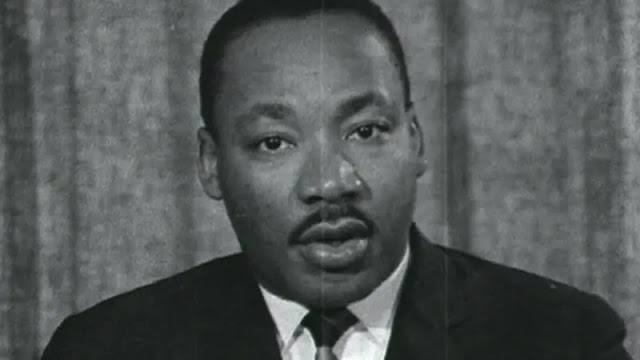

| Martin Luther King's first public speech in the UK at Bloomsbury Baptist Church, October 1961 |

A sermon given during Holy Communion (BCP) at St Giles-in-the-Fields on Sunday 25th August 2024, The Thirteenth Sunday after Trinity based on the text of Luke 10:23–37.

Drawing on Martin Luther King's final sermon to explore the parable of The Good Samaritan.

St Paul’s Cathedral is gearing up to mark the sixtieth anniversary of a visit by Dr Martin Luther King. He stopped off briefly in London on his way to collect a Nobel Peace Prize and preached there in December 1964.

In the first of a series of events, in a few weeks time, Senator Raphael Warnock, who is a Senior Pastor at the Baptist Church in Atlanta where Martin Luther King first preached and was called to ministry, will give a free talk at St Paul’s. In it, he will explore King’s sermon at the cathedral in the context of the world today - do go along if you can.

While his appearance in the pulpit at St Paul’s was a significant event with over 4,000 in the congregation, King’s first public speech in this country took place three years earlier, in this very parish. He delivered a version of the same sermon ‘The Three Dimensions of a Complete Life’ to a full house at Bloomsbury Baptist Church, just across the road. You may have noticed that earlier this year a blue plaque appeared outside the church, marking the occasion.

Arguably King’s most famous speech - “I have a dream” - was delivered on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington DC at the end of The March for Jobs and Freedom, which took place this week in history on 28th August 1963.

Much less well known is the text of Martin Luther King’s final sermon, given during a speech the day before his assassination in April 1968. Speaking to crowds gathered in support of striking refuse collectors outside Mason Temple in Memphis, Tennessee, King began by recounting a trip he and his wife had made to Jerusalem.

They hired a car to drive the road to Jericho - involving a descent of over 3,000 feet to the lowest city on earth. Known as “the Bloody Pass” in the time of Jesus, it was a notorious stretch where bandits and violent robbers targeted their victims.

King remarked to his wife that he could see why Jesus would choose this threatening stretch of road as the setting for the parable we have just heard. A parable in which a victim of a violent robbery is left for dead, his cries for help ignored by both a priest and a lawyer, before someone from a different race - a Samaritan - stops to provide assistance.

Drawing a parallel with the injustices at the heart of the civil rights cause being faced by the black American workers striking in Memphis, King explained that while we can make up any number of excuses to explain why the priest and the lawyer walked on by, they all pretty much boil down to the same thing. They were scared. Scared about what might happen to them if they stopped to help.

Fear prevented them from being a good neighbour.

And fear does the same to us.

Like a flash, it conjures up a variety of concerns.

We fear for our safety. What if the person on the pavement asking us for something has a knife or some other weapon? We could be injured. Or die. What if they are bleeding and their blood gets on us. Will we be infected with something? What if they are infested with lice or fleas? Will we catch them too? What if they are a drug addict and carrying a dirty needle and it pricks us? Fear for our safety can prevent us from being a good neighbour.

Then there’s the fear of loss. Of being conned into giving away our money or belongings by someone who doesn’t really need it. Someone faking it with a self-inflicted wound. A con artist. Wasting our limited resources that we could use to better effect elsewhere - a fear of loss of opportunity. Fear of loss can prevent us from being a good neighbour.

As can fear of judgement. The potential of being judged by the other people walking past, thinking to themselves - what mugs! Fancy them falling for that scam! Or being judged by the person in need - who might ask us for something we cannot or are not willing to deliver and we will be made to look inadequate? Or even worse, what if we try to help them but fail in the process? We start to judge ourselves and our abilities. No, it’s better to leave this stuff to the professionals. We aren’t qualified to deal with people like this. Fear of judgement can prevent us from being a good neighbour.

Then there’s fear of difference. A deep rooted, primal fear, manifest in art and literature through the centuries as fear of the wildman or the bogeyman. Part human part animal. We shouldn’t have anything to do with people on the street calling out for help. We have evolved beyond the need to scavenge for our existence like wild dogs. This person doesn’t look like they are from around here anyway. They should go back to where they came from and get help there. Fear of difference can prevent us from being a good neighbour.

As can fear of change. I have no idea how long it will take to deal with this person. It could take ages and I’ll have to change my plans for the rest of the day. No, I can’t drop everything, I don’t have time to deal with them. If it was someone I knew of course, it would be different matter.

Fear - in all its diverse forms - can prevent us from being a good neighbour.

In his book ‘Beyond Good and Evil’ the nineteenth century philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche argued that the love we show to our neighbours is always contingent upon them meeting certain conditions and that ultimately we show love only to those we do not fear. When we feel a potential threat from that person, we reject them. We condemn them. We pass them by.

Fear, Nietzsche suggested, is thus the bedrock of our morality. Its most powerful force. All our moral and ethical decisions, he claimed, are driven by fear.

Martin Luther King was particularly troubled by philosophies like this. In his final sermon, without mentioning Nietzsche by name, he offers a clever critique and reworking of his thesis.

Fear is at the root of the morality of this parable, King appears to agree with Nietzsche. But, he continues, the issue is not how to rid ourselves of it but to learn how to harness and master it. Instead of fearing for ourselves - for our own safety, for our loss, we are encouraged to follow the Good Samaritan to fear first for the other person - the injured, broken person on the roadside. To fear for their safety. Fear for their loss. Fear for how their life might have changed as a result of the attack. And to use that fear to drive our response.

The question, Dr King explained, is not ‘if I stop to help, what will happen to me’ but ‘if I do not stop, what will happen to them?’ That is life’s most persistent and urgent question, he said.

King knew - and urges us to find the courage to believe - that love (and not fear) is at the root of our morality. Its guiding force. He spent a lifetime sharing it.

And in his final sermon, given a day before his assassination, he encourages us to go and do likewise.

Image: Martin Luther King speaking at Bloomsbury BaptistChurch, October 1961

No comments:

Post a Comment