|

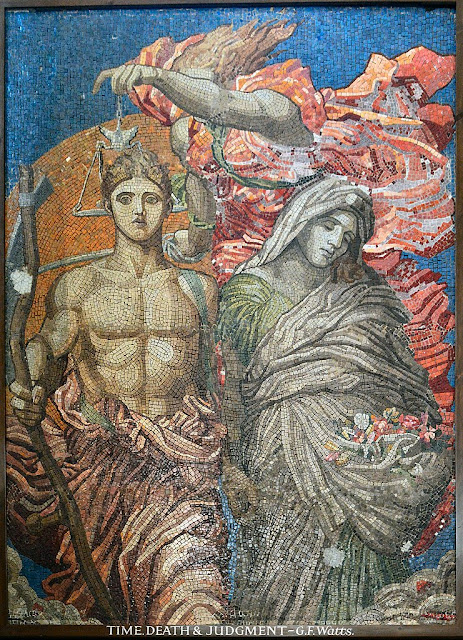

| Time Death and Judgement by George Frederick Watts (now hanging in St Giles-in-the-Fields) |

A sermon given during Holy Communion following the Baptism of Nicola Pitts on the First Sunday in Advent at St Giles-in-the-Fields on 1st December 2024 based on readings from Romans 13.8-14 and Matthew 21.1-13.

Drawing on the changing symbolism in the art of George Frederick Watts, whose work hangs in St Giles-in-the-Fields to explore the Prayer Book readings for the First Sunday in Advent.

Born in 1817 on the same day as Handel - and named after him - the “poet

painter” George Frederick Watts became known as “England’s Michelangelo”.

Put off organised religion as a child by his sabbatarian father’s suffocatingly

strict Sunday routine, Watts nevertheless portrayed religious themes in his

artwork throughout his adult life. A master of symbolism, he sought to depict

the essence of faith through allegory. “I paint ideas, not things” he said. “My

intention is less to paint works that are pleasing to the eye than to suggest

great thoughts which will speak to the imagination and the heart and will

arouse all that is noblest and best in man.”

An ogreish, bulbous and rouge depiction of Mammon seated on a throne of human

skulls is his reaction to the dehumanising effects of Victorian

industrialisation.

His depiction of the “Spirit of Christianity” as an androgynous figure

gathering into its robes four naughty cherubs - representing bickering churches

- a commentary on the futility of sectarianism; his attempt to shame mankind

into growing up and becoming more tolerant.

His work inspired and baffled audiences around the world in equal measure. He

was the first living artist to be offered a solo exhibition at the Met in New

York but refused the invitation of official honours from Queen Victoria.

Towards the end of his life he created an interactive, living

artwork - although always refused to describe it as such. One that tugs on the

heartstrings so immediately that its symbolism needs no deciphering. Known as

“The Peoples Westminster Abbey” it is formed of a series of plaques under a

modest canopy in Postman’s Park in the City of London and honours humble,

everyday heroes who sacrificed their lives to save others. Such as Alice Ayers,

a servant girl who died while rescuing her three nieces from a fire in Union

Street near Borough Market in 1885. Watts conceived of this ‘monument to

unknown worth,’ designed the structure and paid for the first four plaques

himself.

A humble man,

perhaps he wouldn’t be too offended that one of his most famous pieces - in the

form of a mosaic copy - now hangs just through those doors, slightly obscured

from view on the south gallery stairs here at St Giles-in-the-Fields.

In it, Time, Death and Judgement are personified - although you’d be forgiven

for standing in front of it and asking “Who is this?” To the untrained eye like

mine - the classical symbolism is hard to decipher.

Time is

portrayed as an athletic young man brandishing a scythe, striding forward

resolutely in a relentless march. He holds hands with a female figure. Grey and

lifeless, Death gazes down wistfully at freshly cut leaves, flowers and

blossoms; suggesting she can reap her harvest at any time. Judgement flies

above the two, holding aloft a set of scales. Its face masked from view,

symbolising impartiality.

The mosaic which now hangs on our stairwell is one of a number of versions

Watts made of this allegorical painting which, he said - before he created

Postman’s Park - is one of the images through which he wished to be

remembered as having been a ‘real artist’. I rather feel his ‘memorial to

unknown worth’ in the park warrants that accolade more conclusively.

Like Watts’ symbolic artwork, the Prayer Book’s selection of readings today

simultaneously inspire and baffle us - and embody the themes of time, death and

judgement.

As we begin Advent - a period of expectant waiting for the birth of

our Saviour - the gospel transports us to Palm Sunday and Christ’s triumphal

entry through the Golden Gates of the Temple.

We are reminded of the preparation, for that journey - the search for the

humble donkey in order that the prophecy of Zechariah about the coming of the

Messiah might be fulfilled.

We recall the frenetic activity that heralded his arrival; the cries of

“Hosanna”, the spreading of cloaks and branches at his feet. The King James

Bible tells us the whole city was ‘moved’. Other translations are less ‘demure’

- the city was stirred, in turmoil and thrown into uproar.

Everyone was caught up in the power of this symbolic procession. All the signs

were there. But they still had to ask “Who is this”?

As we prepare to celebrate Christ’s birth, the gospel transports us forwards in

time to a pivotal moment before his death, when he was misjudged and abandoned

by those who knew him best.

The reading from St Paul’s Letter to the Romans - on which Cranmer based his

Collect of the First Sunday in Advent - draws on the same themes and likewise

teleports us into the future.

Wake up! Paul declares - the end of time is at hand.

So let us fulfil the promises we all made at our baptism - and renewed a few

moments ago as Nicola was baptised - when we symbolically put to death the

darkness of our mortal lives and rose again to walk in the light of

Christ.

Like the

residents of Jerusalem we are called to be moved - stirred - thrown into a

frenetic exchange of love.

The essence of our faith - which George Frederick Watts came to realise is best symbolised not

through clever allegories from the classical age, but embodied in the sacrifice

of those memorialised in Postman’s Park.

These noble acts of heroism constantly recurring in our everyday life, Watts

explained, should be perpetuated and honoured - as they illustrate our true

character.

As St Paul says, nothing else matters now except to love one another.

So that at the impending day of judgement we may be found worthy of the eternal

life our Saviour has promised.

Like George Frederick Watts, perhaps those who assembled the readings for today

sought not to instil in us ideas that are comforting but to suggest “great

thoughts which will speak to the imagination and the heart and will arouse all

that is noblest and best in man.”

As we open the first door on our Advent Calendars, bedecked with saccharine

symbols of a snowy yesteryear; as we enter this season of anticipation of the

moment in which Gods divine love was enfleshed in the birth of Christ - our

texts today are calling us towards a spiritual maturity.

That, like George Frederick Watts, we may come to know that the innocent divine love born in a manger cannot be fully understood without embracing the reality of Christ’s sacrificial love in his death and resurrection - and the great gift of his Spirit that followed. A spirit that since our baptism is now enfleshed in us - and which we are called to share - to the exclusion of everything else.

The next time (or perhaps the first time?!) we stop to marvel at the symbolism of George Frederick Watts’ great mosaic on the stairwell here at St Giles, may we each see ourselves as living expressions of the ultimate creative act and aspire to form part of the living memorial that is the community of all baptised people - Christ’s love enfleshed on earth.

Then we might be better prepared to answer the question, “Who is this?” when he comes before us.

Amen.

%20by%20Thobias%20Minzi,%20Tanzania.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment