|

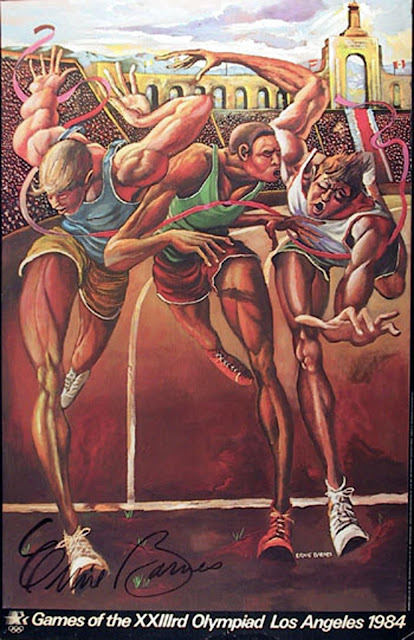

| Ernie Barnes, 100m Sprint, Poster for the 1984 Olympic Games |

A sermon given during Holy Communion at St Giles-in-the-Fields on Sunday 28th January 2024 (The Sunday called Septuagesima) based on readings from 1 Corinthians 9.24-end and Matthew 20.1-16

The blockbuster film Chariots of Fire is a dramatisation of the story of missionary and athlete Eric Liddell and his progress towards the race of all races - the Olympic Games of 1924 held, like this year, in Paris.

In

the film, that isn’t the only race that Liddell and his team mates are running

- not all of which have a clear course.

The

opening scenes are set in Cambridge, and in a speech given by the college

master at the Freshers Dinner, the shadow of the First World War looms large. Throughout,

there is a sense that individuals, institutions and the country as a whole are

caught between the desires to run away from and back towards the recent memory

of that global catastrophe - as another band of young men begin training to

return to France, this time as athletes.

At

a personal level the film reveals competing pressures within Liddell himself -

on the one hand the desire of his family for him to join them at their Mission

Station in China - on the other, his desire to keep running; to win the Olympic

race. Liddell’s sister fears his commitment to training means he is running

away from Christ and his duty to serve the church. Eric tells her that when he

runs he “feels God’s pleasure.” “To win is to honour him” he says. But it is

unclear to us at that point - and perhaps to Liddell himself - which race he’s

talking about.

For

a time, the evangelistic opportunities offered by his notoriety as an athlete

provide a way for Liddell to hold the course of these two races in parallel -

to run them simultaneously. His appearances after each competition helping to

spread the Good News and raise funds for the Mission.

But

he reaches a crossroads in Paris. When the 100 metre heats are scheduled to

take place on a Sunday. Despite pressure from the influential members of the

British Olympic Committee, Liddell refuses to compete on The Lord’s Day.

He

makes the difficult decision as to which race he’s really running.

In

our epistle today, St Paul describes a similar choice - faced by

himself and the church in Corinth, where the Isthmian Games were held the

year before and after the ancient Olympics.

Paul

contrasts the “corruptible crown” - the laurel wreath awarded to the winning

athletes - with the “incorruptible crown” of eternal life - the prize for those

who run the divine race.

Paul

explains that the choice we make about which race we are running has real

consequences for how we live our lives. He’s not air punching or play fighting.

He’s got his gloves on and is hard at work training. Studying the scriptures -

preaching the Good News. Because this is the real deal - the

Olympic Games - not an egg-and-spoon race. He implores us to treat the

Christian life in the same way.

In

Chariots of Fire the story of Liddell is contrasted to that of Harold Abrahams.

His struggle to gain a place on the Olympic team - his desperate need to win -

characterised as a way of overcoming what he describes to his roommate as the

helplessness, anger and humiliation he faces every day as the son of a

Lithuanian Jew.

This

institutional anti-semitism is expressed in a scene when Abrahams is called to

a private dinner with the Masters of Caius and Trinity, at which they accuse

him of not being “English” enough - more focussed on individual than

institutional glory. A self-serving trope still used in thinly-veiled

hate-speech today. One reason why Holocaust Memorial Day - marked yesterday -

remains so important.

Abrahams

responds forcefully to their accusation. “You yearn for victory…with the

apparent effortlessness of Gods” he says. The Dons represent the archaic,

aristocratic age of privilege - Abrahams is at the starting blocks of the

modern, meritocratic era of the future

Their

fascinating, uncomfortable exchange highlights how our conception of the races

we run in life; how we view our interaction with other participants, their

motivation for the prize, their deservedness to win, is subject to deeply

rooted influences. But it is possible, as Abrahams shows, to find the courage

to go against the grain.

Anyone

who went to school at a time when PE lessons involved team captains selecting

from a line-up of classmates - one of whom suffers the ignominy of being picked

last - will have a particular insight into our gospel reading.

We

find ourselves out in the early morning with a vineyard owner picking out

day-labourers lined-up in the market-place, employing those selected in return

for the usual daily wage. Several hours later he goes out again to pick more

staff, this time agreeing to pay whatever is right. He makes three further

trips to the market-place - the final time just one hour before the end of the

working day. On this occasion, the vineyard owner asks why these labourers have

been standing in line all this time? Because no-one else would hire them, they

reply.

At

sunset, the vineyard owner asks his manager to pay the staff. Those who had

worked since the early morning are the last to receive their dues. While

waiting in line to be called forward, they see those who had worked a fraction

of the time being given what they had been promised in payment - so they expect

to be paid more. When it is finally their turn to meet the manager, they too

were given the usual daily wage.

They

complain that they have been treated unfairly. They were entitled to more pay

than the idle labourers who were only in the vineyard for an hour at the cool

end of the day.

In

response, the landowner explains that no injustice has been done. He has paid

them the agreed rate - and in any case, he has the right to use his money as he

wishes. He goes on to suggest that the cause of their anger is not that they

have been treated unfairly - but that they are jealous of his generosity

towards those who found it harder to find work.

How

do you and I, good Christian folk, respond to this parable?

I must admit my gut reaction is to feel sympathy

for the workers who have toiled in the heat of the day and expected to be paid

more. The fact that those who arrived in the vineyard at the eleventh hour are

paid the same doesn’t seem all that fair - to me.

In Chariots of Fire, Eric Liddell shows us that we

may be engaged in many races in life - and sometimes we can run these

simultaneously – each course in parallel. But there comes a moment when we have

to make a choice about which one we’re really running. As St Paul’s letter to

the Corinthians makes clear, we have to engage with that race seriously. In the

film, Howard Abraham’s’ encounter with the Dons reveals how cultural

conditioning can have a pervasive impact on how we view all the races in life - whether we run them or not.

Perhaps

I’ve been running the rat race for so long that it has coloured the way I see

all races - all struggles - in life; including

the divine race? Instead of giving thanks that the workers left standing in the

market-place all day had received a sustainable living wage, my first reaction

to hearing the parable is usually one of annoyance that those who had toiled all day didn’t

get more!

In

life, we can choose which race we really want to run. Like the decision we make

at baptism. We can keep an eye on the right prize as we gather at the altar.

And for a time we can keep running this race in parallel with others. Our

readings today encourage us to ask ourselves whether we are taking it seriously? Are we treating it like the Olympics - or an egg-and-spoon race?

Taking it seriously means training - to pray, to

study, to be willing to confess our sins - to overcome our cultural

conditioning - our sense of entitlement - and learn to engage with the divine

race on the terms Christ has established. Only then will we have the chance to

“feel Gods pleasure” as we run. Only then can we truly honour God - to use

Liddells phrase.

As

well as challenging us, our readings today assure us of Good News, especially for those, like me, who seem to be among the last to put down our egg and spoon. While the

starting gun of the divine race was fired 2,000 years ago it is possible to

make up ground. No matter how conditioned our thoughts and actions have become

by the various races we engage in for money, status and power in the world

today. Because God’s mercy and grace is so bewilderingly great that it still

shines through all that. Revealing uncomfortable truths about how we’ve veered off track

- but also allowing us to see, when we turn around and look back - that his Son is there behind

us, encouraging and supporting us as we take each step closer to the Kingdom.

Where the last

shall be first and the first shall be last.

Image: Ernie Barnes, 100m Sprint, Poster for the 1984 Olympic Games

No comments:

Post a Comment